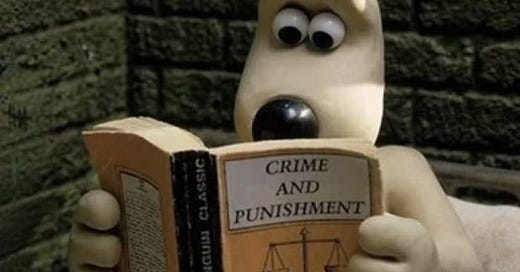

So I read Crime and Punishment

there was no better title, this is a book review, nothing clickbait to see here.

So my journey with russian classics dates back to the COVID-19 year, 2020, according to the very debatable Christian calendar we’re following. I started with War & Peace. I know what you’re going to say, ‘how did you get so low in life that you thought reading War and Peace was a good use of your time?’ I was fretting with the delusional fever of Rodyon, pushing through each page of people sitting stiffly in rooms and never saying what they really want to say to one another.

So, conclusion, my history with the Great Russian Classics didn’t start on the best foot. But I’m lenient, I’m forgiving, I gave it another try with Crime and Punishment.

If you think this is my first Dosto, you’ll be dead wrong. I read White Nights (before it became trendy, but yes, it’s worth the hype), and I also read The Meek One, another short story of his, and I loved it too. I fell more particularly in love with the ambivalence his characters had, the tortured soul, and the gorgeous writing, of course.

I tried reading Crime and Punishment last summer (it is a summer read, everything in the book happens during the summer, so idc what ya’ll say) and I had to DNF it because I found it boring. I DNF’d it right at the moment that Rodyon, our main character, kills the two women who will come and haunt him.

Let me tell you, I have been missing out on some good shit because the story actually gets good after the 200 pages mark. I know, it’s a lot to ask of a reader these days to stay and read 200 pages of a tortured character going back and forth on whether he should commit a murder or not when we already know he’s gonna do it, but trust me and do so.

Dostoevsky’s pen is sharp, incisive, precise, like a surgeon, cutting straight to the bone,

“He was one of that numerous and diverse legion of vulgarians, feeble miscreats, half-taught petty tirants, who make a point of instantly lashing, onto the most fashionable current idea, only to vulgarize it at once, to make an instant caricature of everything they themselves serve, sometimes quite sincerely.”

Isn’t that a BAR? Isn’t that reflective of most people on Substack?

Anyway, moving on from the gorgeous writing because who cares about beautiful writing if there’s nothing interesting to describe (not a dig at Proust).

Well, Dosto uses his writing ability to its highest form by projecting us into the head of a very sick man, someone who’s tortured both with a desire to live, and a desire to see his suffering end by denouncing himself. You are projected into his every thought, and it’s so much at times that it made my head spin (also, I was drinking vodka while reading this, so that didn’t help).

This book is beautiful and a touchstone of literature. It can never be replicated or adapted in its true form, because so much of what is happening happens inside the characters. I’ve read over 1000 books in my life, and nothing has felt the same.

It’s unique and genre-bending in its exploration of the human psyche. It’s also very approachable, unlike his other, bigger works, which are a lot more complex and dense. Yes, it’s confusing when characters have three different names, but Dosto makes sure to use two different names on the same page to be sure the reader knows who he is talking about, because you’ll at least recognize one of the two names. I wish Tolstoy did the same because War and Peace was so fucking confusing at times.

I’ve never read a book that went so deeply into what the human was feeling and thinking, something so vibrant with life and despair at the same time, and it’s quite an achievement.

I wish I had a hot take to share with you, oh wait, there is one: the sister is a closeted lesbian, although she does get married by the end.

You were going on twenty when we saw each other last : I already understood your character then (…) I know my sister would sooner go and be a black slave for a planter or a Latvian for a Baltic German than to demean her spirit and her moral sense by tying herself to a man she doesn’t respect and with whom she can do nothing - forever, merely for her own personal profit.

Dosto writes women with such respect and empathy for someone so dated, there’s a scene at the beginning of the book in wish Rodyon, our main character saves a girl who’s been abused, and he befriends a prostitute (with whom he will become emotionally entangled) and he doesn’t see class and social status as something that matters in his modern society.

The women of this story all get their time to shine, and they all get their own stories even though they’re not the main protagonists. There’s no such thing as a ‘female nature’ in Dosto’s books, yes, the women cry a lot and are more prone to emotion, but they’re also given a reason to: seeing a brother/son for the first time in years, losing a husband/parent. If anything, the women of this book are tragic characters, just like the main character, and I loved to read a classic that wasn’t so outwardly sexist.

Although if you’ve read White Nights, you already know that Dosto sees the profundity of the female experience as well as he sees the depth of men’s.

In conclusion, I thoroughly enjoyed this book. I wouldn’t call this a favorite and find it hard to recommend because it is a difficult book to get through in a way, but if you’ve already been thinking of picking it up, don’t hesitate any longer. Do yourself a favor and devour this book with all of its tension and insanity.

From Marseille with Love,

*vapes away*

(warning ramblings of a person who studied russlit in uni ahead) a little bit on the naming structure you pointed out: dostoevsky actually changes the way the narrative addresses a person depending on how the person the story is focusing on feels about the person! for example if raskolnikov is thinking of his sister through the narrative (i.e. his thoughts appear outside of the confines of quotation marks) the diminunitive "dunya" is used, whereas if razumikhin is thinking of her the name "avdotya romanova" is used because he respects her a lot, so he uses the more formal name/patronymic structure. all this to say dostoevsky's exploration of the human psyche as you noted is even embedded in the semantics of the story! so cool! anyway loved the review, definitely a fun first read of your page!^^

I’ve started reading your posts recently. I’m glad I discovered you. I get the experience of talking to someone who is really different from me, but whose take, point-of-view, and insights lead me to rethink my own. You also make me laugh at myself which is a good thing. I read Crime and Punishment the first time a zillion years ago when I was nineteen. I’ve since read it a couple more times—once in my late 40s and once more in my mid-fifties. The first time I read it, I read it shortly after Jude the Obscure. Those two books, taken together, really convinced me that I was not the only person ever to feel what I felt. There is nothing lonelier than that kind of novelty, like you minted your own special misery.